Tuesday, July 04, 2006

Monday, July 03, 2006

Working hard for her own pleasure

SHE BENDS OVER THE UTILITY SINK, her galvanized bucket receiving a stream of scalding hot water, and pours granules of Spic-N-Span through the clouds of steam.

On this average 1950s Saturday night, in her small town, she sets up her tools, preparing for the task ahead.

Like all the other farmwives, she has lived through a week of dirty boots tracking mud across her floors, spilled milk, and wrestling children. The black-and-white checkerboard of the kitchen floor is covered with the evidence.

Like all the other farmwives, Sunday is her day. In the morning she will put on her seamed stockings and her best dress, and she will go to church.

After the service is over, after the men have stood in circles and smoked outside, after the weather has been discussed and diseases of cattle reviewed, she will go back to her house. Someone will come by—the minister, some in-laws, someone she sees only on Sunday at church—and she will serve them coffee, and the cake she made for Sunday.

But before her company arrives, she will put her house in order. No matter how tired she is, no matter how much work she has done, on Sunday morning her kitchen floor will be clean.

So on Saturday night, after all the children are bathed, their hair wound into pincurls, their tiny Sunday clothes ironed and hung up for tomorrow, she mops the floor.

And in all the other farms for miles around, lights glow from kitchen windows, making silhouettes of farmwives, mothers all, dedicated workers with reddened hands, purposefully stroking ragmops across old linoleum, bending over steaming buckets, their last task before sleep and a Sunday of rest.

IF SHE WANTED TO, MY MOTHER COULD STILL MOP A MEAN FLOOR. In a few days, she will be 73 years old, but her years at hard labor on the farm have only made her strong.

Now she has a no-wax floor, but it still needs tending, and she still frets after a week of grandkids, a mud-footed husband and good old Wenatchee clay have left their marks.

I keep this image of my mother because she still mops the floor, and she does it with the same pride and craftsmanship she demonstrated on the old farmhouse linoleum.

It’s not so much that I want to be a good farmwife and mother or match my mother’s energy level. And I confess: I do not mop my kitchen floor once a week.

In a sense, I learned more about meeting goals and getting things done from watching my mother on Saturday night than I ever learned after we left the farm.

That floor had to be mopped, not to teach her daughter a lesson about work, or even to make a favorable impression on the neighbors. It had to be mopped so my mother could have time to herself, to create a pure spot of joy in her hard life.

When she woke up a few hours later she could indulge in a moment of pride, standing in the kitchen doorway and seeing the pristine white squares against the shiny black ones. She had done a hard job well for her own pleasure.

WHEN I MOP MY FLOOR, IT’S NO ACCIDENT THAT I DO IT ON SATURDAY NIGHT, with all the lights off in the house but the one in the kitchen. And while I stroke my modern sponge mop across the black-and-white squares of my no-wax vinyl, I fall into a trance made of love and reverence for my mother.

I HAVE WRITTEN THIS STORY IN MY HEAD on every Saturday night that I mopped my own floor, trying to imagine how it felt to be a woman with eight children, living on a farm in the 1950s.

Like any good daughter, I feel shy but intrigued when I try to stand in my mother’s shoes. But I do know how she felt, because she still feels that way today.

When I go to visit after she’s cleaned the kitchen, she says, “Look at my floor! Isn’t it clean?” After all these years, it still brings her joy.

She taught me how to mop a floor, but that’s not all I learned. My mother taught me how to do a hard job well for my own pleasure.

Looking for Jack

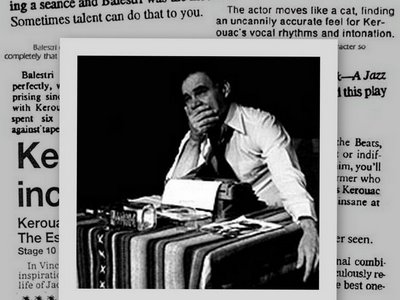

Kerouac: The essence of Jack

A jazz play by Vincent Balestri

Velvet Elvis Arts Lounge Theater

107 Occidental, Seattle, 206/624-8477

Playing now through February 1997

I wrapped my coat tight around me against the cold wind coming off Puget Sound and walked from the bus stop under a bridge through bodies lying on the ground in sleeping bags under boxes on downtown Seattle sidewalks heading downhill to meet up with Jack. “Cold enough for ya?” asked one wino now known as Homeless Man in the politically correct Nineties as I passed him by wishing I hadn’t worn these heels that caught on the bricks of the streets in the old underbelly of town.

The outside walls of the theater were plastered with reviews I read shivering, not from cold but from anticipation and sheer living thrill, nervous as a virgin, hoping he would be there soon, hoping he would speak just to me.

A crowd of bobbing black berets, old and young, dressed by nordstroms, nordic-looking northwesterners surrounded me, staring into the black box office hole where will-call tickets were waiting. The window opened; the door opened; the polite queue formed one line and filed in.

A jazz trio played on the stage as if they were unaware of the people coming in. The crowd bustled, rustling 8-page programs, reading about Jack and his family, and how this Essence came to be. No whisky, no beer, no sweet tokay, just a quiet little jazz group, modern white hipsters, drums bass and sax until the horn player stopped. He walked to the edge of the stage and said, “Hey Jack….Jack? Are you coming in?”

A few seconds later a stocky dark-haired man took the stage as the house lights went down, raising his arms like a maestro, his back to the people, commanding the boys to play bebop as he danced spastically, kicking out his feet left and right like a guy who can’t dance but must dance because the music says go man go!

In a voice made of flat chicago As and lowell Ahs he speaks to the crowd: Jack Kerouac, thanking us for coming, thanking the band, thanking the actor who will play him tonight. He explains that the play will have two parts; the first part, he says, will take him through his one-page biography up to publishing On The Road. “Then we’ll have an intermission,” he says, grinning insanely,“ and when we come back, you can ask me some questions and then I die.”

He peels off, burns rubber and dances, writhing, his back to me, a mad wordless prologue made of this stage, a desk, a bookcase, empty bottles of whisky and wine, a dervish in a white shirt and black chinos, possessed by a spirit, maybe The Spirit, I don’t know, but there’s no turning back now.

For the next two hours he reads, talks, carries on imaginary conversations with Gerard, his father, his mother, his wives. He comes down off the stage and embraces hands in the first row, cupping one hand inside his two, speaking quietly sometimes seeming afraid, then leaping back onto the stage, vamping wildly, a madman trying to appear normal, a little boy seeking love, a shy messiah checking for blood stains on his hands and feet and finding it not there but on the hands and feet of those he lived with, escaped from, lost.

He weeps, bangs, sweats, transcends, suspends disbelief, reaches satori in seattle transformed as people shift in their seats unable to take their eyes from the stage.

I find my breast swelling with sadness over and over again, my heart aching, tears welling up in my eyes. I want to yell, “JACK! Wait! Don’t go….” But he does, yet he is, and as every memory I have of the 50s and 60s stampedes through my psyche he descends into the end of his life and dies.

I missed him again, I think to myself. As in life, where he was dying from drink just as I was finishing On The Road, here in the Velvet Elvis theater he died again, looking right through me toward his destiny with the Sal Paradises and the Dean Moriartys and beer belly bars in Florida.

What did I want to learn about him that night? The others had asked him about LSD, Burroughs, Buckley. I blurted out, “Did you ever love anybody?”

Yeah…of course I did…” he said, his eyebrows knitted up in confusion and sadness, as if I had betrayed him, and his eyes drifted away from mine and he looked at his feet. “Yeah,” he said, all trancelike, “I love all of you…”

It was over for me then, but I stayed until the performance ended, wondering why I’d asked that question. He owed me nothing, and in a very real sense, I owed him everything that I have as a writer, the very structure of my life since 1969, the people I have known and loved, the travels I have taken, the way I look at living.

Outside of the theater I felt suddenly disconnected, wanting looking seeking wordlessly aching. I’m not one for pilgrimages, or meshing fantasy with reality, and I had never really wanted to meet Jack or even have some silly souvenir to make him seem more real. But for many years I had felt ambivalent about him--his writing, his life, his influence--and he’d sort of drifted around insignificantly in my consciousness.

Jack Kerouac was more to me than a footnote. But I was trying to deny what he meant to me, and standing outside in the surreal winter night I heard him say what I felt: “I have nothing to offer anyone except my own confusion.”

Vincent Balestri made Kerouac come back to life—no mean feat, considering the seemingly endless individual interpretations of who Jack was. He honored him and his life and his death. He made me believe. He forced me to look within again for honesty and courage, as Kerouac had done so many years ago.

What I really found that night when I went looking for Jack was that my questions will never be answered unless I answer them myself.